Finger on the pulse

Learn how your chickpea hummus is creating more sustainable farming systems.

The advice we so often hear given to people who want to reduce their environmental footprint is “stop eating meat”. Those who do try to give up meat still need to consume protein, so they’ll usually turn to a source like chickpeas and lentils.

But did you know that eating chickpeas and lentils could be contributing to creating more sustainable farming systems? And, it’s got nothing to do with replacing meat.

The magic of pulses

A ‘pulse’ is a term used to describe a grain-producing legume. If you need a refresher on what’s so special about legumes, here’s a quick refresher.

Legumes, like snow peas and green beans, have an incredible ability to form symbiotic relationships with microorganisms in the soil called rhizobia. Basically, legume roots exude an enzyme (flavonoids) in the soil which attracts the rhizobia. When the rhizobia connect with the root hairs, the legume can form special root structures called nodules to ‘house’ the organisms.

From there, the real magic begins.

The legume converts sunlight into sugars through photosynthesis and trades some of this energy with the rhizobia. What they’re trading for is nitrogen in the form of ammonia.

Rhizobia have an incredible ability to pull from the air the nitrogen that makes up 78% of the Earth’s atmosphere and store or ‘fix’ it in the soil, inside these newly-formed nodules.

To put into context just how incredible that is, consider this. Humans also know how to pull nitrogen from the atmosphere, and do it every day to create synthetic fertilisers.

In order for us to fix nitrogen, we need to create temperatures of 450 degrees Celsius and a pressure of 200 atmospheres.

Rhizobia do the same thing, at 1 atmosphere, in soil that’s about 15 degrees.

So, the fact that pulses like chickpeas and lentils can partner with these organisms and make use of the nitrogen is something special.

The rise of pulses

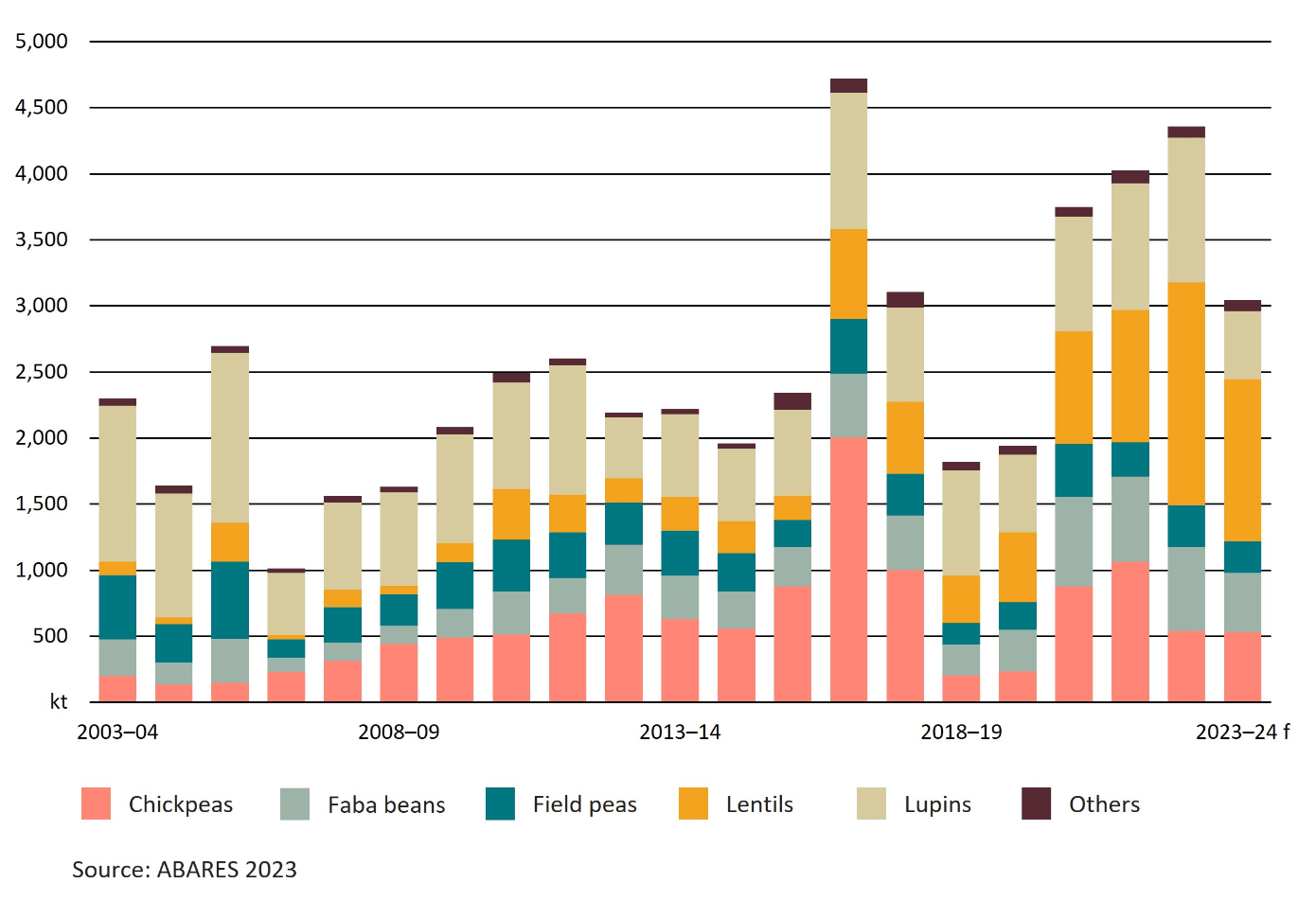

Pulses started cropping up (pun fully intended) in Australia around the 1960’s and 70’s and production has steadily grown since.

While the volume produced each year is dependent on seasonal conditions, there’s been a clear trend over time to plant more area to pulse crops.

Let’s take a look at a few of the reasons why pulses have been increasing in popularity, and how they could be contributing to more sustainable systems.

Less nitrogen fertiliser

First, the pulse crop needs little to no nitrogen fertiliser itself, since it’s fixing atmospheric nitrogen that can often provide for most or all of its needs.

Second, a really efficient crop can fix excess nitrogen that it doesn’t use itself - on average about 50kg/ha in low rainfall systems. This nitrogen is left in the soil when the plant dies and becomes available for the next crop to use, meaning it can reduce fertiliser requirements for the next crop. This depends a lot on the type of pulse, the seasonal conditions, and the amount of nitrogen in the field when the crop is planted, but it is very much possible under the right conditions.

Fighting weeds and pests

Pulses are often used as a “break crop” in cereal rotations. If cereal crops are grown in succession, the field can often develop issues with grass weeds as they can’t be sprayed without killing the cereal crop.

Planting a pulse crop provides an opportunity to use a selective herbicide to target grass weeds and reduce pressure on future cereal crops.

There is also great concern at the moment over herbicide-resistant weeds and pesticide-resistant insects. Anytime a product is sprayed in a paddock, you’re selecting for resistance (by killing off most of the pests/weeds and leaving only those that have resistant genes, that can then reproduce).

That means the best way to reduce resistance is to reduce the frequency of spraying the same product. Building crop rotations with multiple types of plants (like cereals and pulses) allows the farm manager to rotate the suite of chemicals they’re applying and reduce the risk of developing resistance to any particular product.

You may not like the use of herbicides and pesticides, and their use certainly needs to be minimised, but it’s in everyone’s best interest that when we need them, they work.

Boosting farm profitability

Through the effects mentioned above of providing nitrogen to the soil and reducing weed and pest pressure on subsequent cereal crops, pulses can increase the overall profitability of a crop rotation.

A trial in Mildura found the inclusion of a pulse crop in a cereal rotation could boost wheat yields by 0.6-1.6t/ha (albeit off a low base) and gross margins by ~$80/ha/year.

Pulses can also be a highly profitable crop in their own right, with a strong export market into countries such as India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.

Growth likely to continue

It’s no surprise given the benefits to both consumers and farmers that pulses are expected to continue their rise in popularity.

The global pulse market has been growing at 1.7% per year over the last decade and is expected to continue because of their credentials as healthy and environmentally-friendly products.

So, it doesn’t always have to be about replacing meat. Encouraging consumption of chickpeas, lentils, and beans in their own right is always going to be a good thing because they’re benefitting farmers and the environment.